- Addison, Joseph: “The Pleasures of the Imagination,” The Spectator, nos. 411-421, June 21 - July 3, 1712.

- Aristotle: On the Soul, trans. J. A. Smith (http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/soul.html).

- Baillie, John: “An Essay on the Sublime,” in The Sublime: A Reader in British Eighteenth-Century Aesthetic Theory, eds. Andrew Ashfield and Peter de Bolla (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- Bruhm, Steven: “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics at the Revolution,” Studies in Romanticism 32 (Fall 1993), 399-424.

- Burke, Edmund: A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. James T. Boulton (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1987 [1958]).

- Burke, Edmund: Philosophische Untersuchung über den Ursprung unserer Ideen vom Erhabenen und Schönen, trans. Friedrich Bassenge (Hamburg: Felix Meiner Verlag, 1989).

- Descartes, René: The Passions of the Soul, trans. Stephen H. Voss (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989).

- Kant, Immanuel: Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis - Cambridge: Hackett, 1987).

- Kant, Immanuel: Kritik der Urteilskraft (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1974).

- Locke, John: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Roger Woolhouse (London: Penguin, 2004).

- Longinus: “On the Sublime,” trans. W. H. Fyfe, rev. by Donald Russell, in Aristotle, Poetics – Longinus, On the Sublime - Demetrius, On Style (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

- Lyotard, Jean-François: Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime (Kant’s ‘Critique of Judgment’, §§23-29), trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994).

The history of philosophy is often rendered as a multi-linear narrative, whose individual storylines are made up of different conceptions following upon one another through a logic of negation. [1] Conceptions included in the narrative are supposed to mark important stages in the development of philosophical thought. It is precisely their capacity for a critical distance from preceding conceptions which earns them a place in the narrative. The history of 18th-century aesthetics is patterned much the same way. As far as Edmund Burke’s aesthetic treatise (A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757/59), and more specifically, its general theory of the passions, is concerned, the text clearly indicates the point of reference from which the author wishes to distance himself: the ultimate target is John Locke (An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690), whose ideas are criticized at several points in Burke’s discourse. At the same time, however, the person negating inevitably turns into the one being negated, when about three decades later, in a seminal section of the Critique of Judgment (1790), Immanuel Kant names Burke as a major precedent not simply to be honored but, more importantly, to be critically surpassed.

Edmund Burke, A Philosopphical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757/59

While the Locke-Burke-Kant lineage is certainly a cliché among historians of aesthetics, oversimplifying the otherwise non-linear and rather complex network of interrelations both in the sources and the reception of Burke’s Enquiry (involving Le Brun, Du Bos, Addison, Hume, Shaftesbury, Baillie, Diderot, Mendelssohn, Lessing, and Herder, among others), it still may serve demonstrative purposes with regard to the notion of distance and the logic of distancing.

Burke/Kant

Kant’s polite but highly resolute gesture of distancing himself from Burke is something of a common-place, but it still makes one ponder for at least two reasons. It deserves scrutiny, because, on the one hand, both Burke’s and Kant’s argument centers on the idea (or rather, the hardly granted possibility) of distancing or distanciation, and on the other, because such seemingly interpersonal relations are not necessarily limited to connections between two persons.

One could argue, for instance, that the same displacement (from empiricism to transcendental philosophy), which appears as an interpersonal difference between Burke and Kant, could in fact be discerned within Kant himself as a passage from so-called “precritical” to “critical” philosophy. In this respect, Kant’s biographic reference to Burke is but the projection of an autobiographical relationship, as if the sage of Prussia rejected, in the image of his Irish colleague, his own younger self (the naïve thrust of his own Observations on the Beautiful and the Sublime, 1764), and as if this gesture of out-placement was needed precisely because the autobiographical relation might make the distancing much more difficult. According to the logic of autobiography, every negation must be a determinate negation (as Hegel tells us) since the negated element determines its own negative. And since the negative (as a determinate negative) is an heir to, or survival of, the very element it negates, the latter will ceaselessly haunt it, as one of the readers of the Kantian sublime has shown. Jean-François Lyotard claims that, with respect to the passions, Kant is “closely following Burke,” and “no matter what he says,” his conception of the sublime as a “negative pleasure” (negative Lust) is but an echo of the Burkean concept of “delight.” [2]

The need for critical distancing, within an autobiographical relation, also emerges with reference to Burke’s own career, whenever his “early” aesthetic speculations are contemplated, following Burke’s own suggestions, from the perspective of his “late” contributions to political philosophy. This kind of approach is often accompanied by the conclusion (or rather, the presupposition) that the boyish carelessness and radicalism of the Philosophical Enquiry is corrected, as it were, by the mature and deep historical wisdom of the Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), and that thus, in his later years, Burke distances himself, however implicitly, from extremist and revolutionary modes of thought inspired by the sublime. Somewhat less frequent and therefore more remarkable are readings, which – inverting the direction of criticism – analyze the Reflections from the perspective of the Enquiry, submitting to aesthetic analysis his political discourse. Even less frequently, however, does one encounter readings which do not place these two works on a see-saw, praising the one by blaming the other, but rather, uncover different and less distinct relations between them, which are more cumbersome to articulate, but perhaps more promising in their heuristic potentialities.

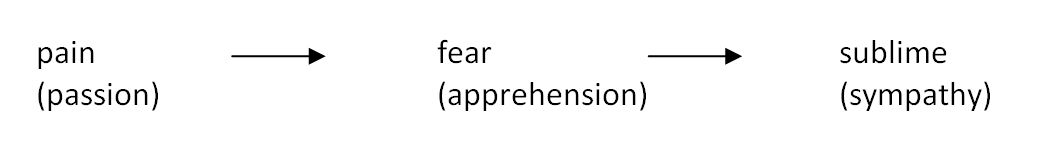

Since critical distance (both along biographical or autobiographical terms) is in fact just another name for the kind of aesthetic distance (distanciation or negativity) Burke and, of course, Kant is talking about, it seems highly practical, if not wholly necessary, for any effort at circumscribing the critical position of the Enquiry, to consider how the notion of distance is inscribed into Burke’s aesthetics. As we shall see, this inscription is far from being a simple or single one, it is rather multiple or multi-layered, which produces a level of complexity high enough to be worthy of a sustained analysis. It is the element of distance which distinguishes the concepts of pain, fear, and the sublime – with fear functioning as a point of articulation dividing as well as connecting pain and sublimity, thereby pointing toward a broader conceptual field, which offers a somewhat less common conception of the passions through the twin concepts of tension and attention.

Locke/Burke

In order to accurately trace the distinctions between pain, fear, and the sublime, and to shed light upon the role played by distance in drawing these distinctions, we first need to get a somewhat detailed picture of the properly Burkean general conception of the passions, paying special attention to elements which mark a move away from the Lockean scheme.

The general theory of the passions, spelled out in Part 1 of Burke’s discourse, has a double function: retrospectively, it continues the project of Longinus, whose fragmented rhetorical treatise breaks off precisely with the promise of an investigation of the passions, [3] while at the same time it prospectively lays down the conceptual fundaments, which are supposed to allow for a sophisticated analysis of the categories Burke himself is about to develop (notably, those of the beautiful and the sublime). Burke outlines the passions according to two different schemes: one could be called “structural,” and the other “thematic.” As opposed to the latter, “thematic” division, which groups the passions either under the heading of self-preservation, or that of society (subsuming the sublime into the former, and the beautiful into the latter group), what we need to pay attention to at the moment is the other division, the one I called “structural,” since that is where the element of distance acquires a key role, as part of a debate with Locke.

Having underlined, in the very first section, the importance of novelty in evoking intense passions, Burke attempts, in the next four sections, to question the popular Lockean idea that pleasure and pain are passions emerging from one another: “Mr. Locke […] thinks that the removal or lessening of a pain is considered and operates as a pleasure, and the loss or diminishing of pleasure as a pain. It is this opinion which we consider here” (Part 1, Sect. 3: 34). [4] The Lockean conception under consideration here presupposes a tightly closed economy of the passions, insofar as any increase in either of the two basic passions is imaginable only in correlation to an equal decrease in the opposite passion, following the logic of expenditure and income. [5] Just as one man’s income is another man’s expenditure, the emergence or intensification of any of the two basic passions can occur only with the simultaneous disappearance or weakening of its counterpart. For Burke, however, passions are subject to a certain amortization or erosion, they get worn with the passage of time (just as coins), without inducing any increase, i.e. any compensation, on the opposite side. The basic form of their emergence is likewise asymmetrical, and in that sense an-economic (just as the minting of coins), since they are in no way, in their occurrence, bound to the partial or full diminishing of their opposites. This is why in their basic form both pleasure and pain are independent, i.e. “positive,” passions. Their positivity resides precisely in their capacity not to emerge from the negation of their opposites:

“Pain and pleasure are simple ideas, incapable of definition. People are not liable to be mistaken in their feelings, but they are very frequently wrong in the names they give them, and in their reasonings about them. Many are of opinion, that pain arises necessarily from the removal of some pleasure; as they think pleasure does from the ceasing or diminution of some pain. For my part I am rather inclined to imagine, that pain and pleasure in their most simple and natural manner of affecting, are each of a positive nature, and by no means necessarily dependent on each other for their existence. The human mind is often, and I think it is for the most part, in a state neither of pain nor pleasure, which I call a state of indifference.” [Part 1, Sect. 2: 32]

Burke questions the economic relationship between the passions under investigation. An increase in pain does not necessarily imply a decrease in pleasure, just as the intensification of pleasure does not involve the lessening of pain. While, for Locke, the total sum of the passions (of pleasure and pain) was at all times constant (according to a principle of passion conservation, as it were), in the Burkean framework, passions can both appear and disappear – an-economically. Once passions can be inscribed or erased similarly to the minting or abrasion of coins, a moment of violence enters Locke’s system. This is how, in their basic form, both pleasure and pain can be considered as “positive” (in other words, “simple,” “independent,” or “unrelated”) sensations, provided that positivity is by no means a category of value, but refers rather to the structural necessity of a moment of violence.

But to be able to introduce the concept of positivity, and thereby distinguish independent (i.e. positive) from relative (i.e. negative) pleasure or pain, Burke first has to introduce a third state of mind, which does not exist in the Lockean scheme. And this is what he calls “indifference,” a state of tranquillity or apathy. [6] It is only with relation to such a state, that any notion of positive pleasure or pain makes sense, the reason being that these sensations do not emerge through the negation of their opposites, but rather appear through a move away from the neutral state of tranquillity, also returning to that state when they vanish. The other passions, which emerge through the negation of their opposites (and are therefore “negative” [7]), are given individual names for the sake of clarity: relative pleasure will be called “delight,” whereas relative pain will be called “disappointment” or “grief.” [8] Once these names are established, the basic forms of the passions can be referred to without the constant use of word “positive,” by calling them simply pleasure and pain.

Thus, with the insertion of the hypostatized state of indifference, Locke’s dichotomous system (pleasure/pain) is extended to involve five elements: beside indifference Burke develops the categories of positive pleasure and positive pain, as well as those of negative pleasure (i.e. delight) and negative pain (i.e. disappointment or grief).

Since the whole Burkean system is based upon the insertion of the category of indifference (for it is that very insertion that generates the disjunction of the positive and negative levels), the status of that category seems crucial. One could easily take it as a metaphysical postulate that has to be granted hypothetically for the matrix to evolve. From later passages in the treatise, however, we might get the impression that there is a different consideration in the background.

For when in Part 3 Burke briefly returns to this concept, he provides an account, which suggests that the state of indifference is by no means a supra-historical state, given by nature, but is indeed a historical formation, a product of custom or use:

“For as use at last takes off the painful effect of many things, it reduces the pleasurable effect in others in the same manner, and brings both to a sort of mediocrity and indifference. Very justly is use called a second nature; and our natural and common state is one of absolute indifference, equally prepared for pain or pleasure.” [Part 3, Sect. 5: 104]

Indifference is nothing but a faded or worn passion, which has lost its power due to the repetition of the affect, and can therefore appear as a “second nature,” in the ideological mask of naturalness (just like the dead metaphors that Nietzsche likens to worn coins). [9] Strangely enough, Burke speaks of “absolute” indifference in the passage just quoted, while his perspective sheds light precisely on the fact that this indifference is anything but absolute: behind its apparent naturalness historical contingency is hard at work. Thus, it cannot be taken as a state “absolved” from all historical reference. Since Burke conceives the passions in their historical formation, his passion theory has in fact history as its latent object.

Pain, Fear, and the Sublime

The above system of the passions, so symmetrical in terms of structure, is determined by a double asymmetry. Firstly, the categories of the beautiful and the sublime are both situated on the side of pleasure – the beautiful being subsumed into the rubric of positive pleasure, while the sublime into the rubric of negative pleasure (or delight). [10] The categories of positive and negative pain are clearly left empty, as if Burke had nothing to say either of actual pain, or of relative pain deriving from the temporary or final loss of the source of pleasure. Secondly, he attributes greater intensity to pain, than to pleasure, [11] so the passion turning on positive pain, that is, the passion of the sublime as negative pleasure, comes to the fore due to its sheer force, as opposed to the passion of the beautiful as positive pleasure. [12] The latter asymmetry is replicated in the thematic division of the passions, privileging the passions of self-preservation over those of society.

As a result of these two kinds of asymmetry, Burke’s structurally balanced scheme begins to slope, as it were, toward its lower left corner, to the rubric of negative pleasure. And since that point can, in turn, be reached only from the diametrically opposite corner of positive pain, it comes as little surprise that later on Burke’s attention is aimed primarily at that movement, the transition from pain to the sublime. This is what happens when in the recapitulatory discussion of the passions concerning self-preservation he writes the following:

“The passions which belong to self-preservation, turn on pain and danger; they are simply painful when their causes immediately affect us; they are delightful when we have an idea of pain and danger, without being actually in such circumstances; […] Whatever excites this delight, I call sublime.” [Part 1, Sect. 18: 51; Burke’s emphasis]

The force of the sublime derives from its connection to pain, while its capacity to cause pleasure implies a mediated relation, a spatial or temporal detachment. It is in such a context that, at an earlier phase, the element of distance enters Burke’s argument:

“When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful, as we every day experience.” [Part 1, Sect. 7: 40; my emphases]

The juxtaposition of the notions of “distance” and “modification” might suggest an interpretation of the former as a strictly spatial notion (as distance per se in the narrow sense), and the latter as a temporal concept. Yet, it seems more likely that within the Burkean lexicon “distance” is meant both in a spatial and temporal sense, [13] while the concept of “modification” refers to the concomitant change in the modality or intensity of the passion, as when he speaks of the “modifications of pain” (Part 1, Sect. 5: 38).

Although the word “safety” appears only once in the discourse, in a relatively late and by no means strategic argument about Locke’s opinion concerning blackness (Part 4, Sect. 14: 143), the notion of safety seems highly important for Burke, since distance is first and foremost a safe distance, whether it is reached in terms of time or space. This is true even though Burke insists that our safety (he uses the word “immunity”) is only a prerequisite for our delight, and by no means its ultimate cause (Part 1, Sect. 14: 48). [14]

More important for our purposes is the fact that the two passages cited above do not resemble merely in their common emphasis on safe distance (spatial or temporal), but also because of a rather disturbing circumstance, one to which interpreters of these otherwise much quoted formulations have paid little attention so far. For, if we dare ask the hardly unimportant question, from what exactly we have to distance ourselves, Burke’s text gives a surprisingly vague answer. For neither of the two passages mentions only pain (or rather, the necessity to distance oneself from pain), but both make mention of danger as well (and of the necessity to move away from danger) – even though they do so in different ways: in a different word order and with different conjunctives, the first one saying, “pain and danger,” the second one, “danger or pain.” [15] But it is far from clear how danger (and the fear or terror evoked by it) is related to pain, since the two different conjunctives (“and” and/or “or”) can mean both the difference and sameness of the conjoined elements, and thus the conjunctives themselves can be both different and identical in relation to each other. The question remains therefore, how pain is related to danger (the sensation of pain to the sense of danger), and how the feeling of sublimity is related to both, whether from the same distance, or not. To answer this question is tantamount to trying to explain why Burke can claim, first, that without distanciation the source of the passion would be “simply painful,” [16] and, second, that it would affect us as something “simply terrible.” Are pure pain and pure terror one and the same sensation, or are they different? And, whatever their relation, are they indeed simply “simple”?

The answer comes at a much later point in the discourse, since the general theoretical matrix of the passions sketched out in Part 1 does actually not spell out the relation between pain and fear. That is exactly what happens, however, at the beginning of Part 4, where Burke’s focus is expressly directed on the difference between these two passions. He examines the similarity and difference between pain and fear in the framework of an argument, whose prime objective is to trace the efficient causes of the sublime – an investigation to be repeated later (in the second half of the same part) with regard to the beautiful. In Part 4, Burke defines fear as “an apprehension of pain or death” (Part 4, Sect. 3: 131), exactly the same way he defined it two parts earlier, in Part 2, in the second section on terror (Part 2, Sect. 2: 57). Fear (or, in its extreme form, terror) appears in both places as the sensation of a sensation, as an “apprehension,” or misgivings, the presentiment of the sentiment of pain. [17] In the state of fear only the idea of pain is present to us, the very pain itself, which we try to evade, is deferred to the future. Thus, there can be no doubt that fear itself is already at a certain (albeit unsafe) distance from pain, so when Burke places the feeling of the sublime not only beyond pure pain, but also beyond pure fear, he in fact puts it at a double remove from actual suffering, suggesting that distance does not necessarily imply safety, but can just as well be a dangerous distance.

According to the logic of this double remove, the sublime is conceived as a distance from a distance. But since the distance to be distanced is an unsafe or dangerous one, there is no guarantee that the secondary distance from this unsafe distance will produce safety. Rather, what is implied is that any effort at distancing from an unsafe distance will itself lead to just another level of un-safety, raising distance to the second power without any ensured move from danger to the pure absence of danger. An unsafe distance from a previous unsafe distance will never add up to safety (no matter on which arithmetic power distanciation is repeated), but will only reproduce danger on yet another level of complexity. As a result, the sublime remains in constant danger of relapsing into danger, and thus, into a state of panic fear. Sublimity is endangered by danger, safety is threatened by threat. That is how the intermediate position of danger or threat (and the attendant passion of fear or terror) gains a special critical importance.

The relation between pain and the sublime – between passion and sympathy, pathos and syn-pathos, or trauma and safety – is articulated by the intermediate state of fear, which functions as a point of articulation not only dividing the two polar positions, but also connecting them. While fear is the sentiment, or rather, presentiment (“apprehension”) of pain, it is still not “simple” pain, as it also implies a certain distance. In this respect, it is something like a distant injury or distant wounding: a teletrauma. Neither is it im-mediate pain, nor is it pure painlessness. It simultaneously involves the mediatedness or structural anaesthesia of any instances of trauma (i.e. the distance of what is near), and the disruption of our safe detachment from events occurring in other spaces or times, through some sort of tele-sensing, or telaesthetic traumatism (i.e. the nearness of what is far away). At the same time that it articulates, it also disrupts the conceptual distinction between pain and the sublime (or, passion and sympathy), and becomes the site of their spectral contamination. Being an amalgam of suffering and anaesthesia, fear may function as a critical tool undoing received notions of perceptual immediacy and aesthetic distance. [18]

What needs to be investigated therefore is why every trauma must necessarily become distant, on the one hand, and why, on the other hand, “sublimation” itself (that is, any form of seemingly intact or anaesthetized observation) must inevitably turn traumatic. Burke’s treatise has much to say about both sides of the problem. That investigation, however, must follow a different line, running along the Burkean notions of tension and attention, and must therefore compose a separate argument, which I have attempted elsewhere.

For an extended version, including a section on “Tension and Attention,” see The AnaChronisT 17 (2012) at http://seas3.elte.hu/anachronist/2012Fogarasi.htm.

Jegyzetek

- [1] This paper is the belated progeny of a research I began to pursue between 2005 and 2008, with the support of a Bolyai Research Scholarship. In its early stages, it was presented, with different accents, at conferences in Athens (2005) and Piliscsaba (2008). For an extended version, including a section on “Tension and Attention,” see The AnaChronisT 17 (2012) at http://seas3.elte.hu/anachronist/2012Fogarasi.htm. ↩

- [2] Jean-François Lyotard, Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime (Kant’s ‘Critique of Judgment’, §§23–29), trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), 24 and 68. ↩

- [3] In fact, Longinus’ treatise does not merely promise the discussion of the passions, of which the author plans to write in a “separate treatise” (Sect. 44: 307), but already signals their place among the congenital sources of the sublime (Sect. 8: 181), sporadically discusses them (Sect. 9-15: 185-225), while at the same time he also warns us that a passionate state is not in itself equivalent to sublimity (Sect. 3: 169-171). Page numbers refer to the following edition: Longinus, “On the Sublime,” trans. W. H. Fyfe, rev. by Donald Russell, in Aristotle, Poetics – Longinus, On the Sublime – Demetrius, On Style (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995). ↩

- [4] All page numbers refer to the following edition: Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. James T. Boulton (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1987); this is a re-edition, with a revised introduction, of the 1958 critical edition of the Enquiry, also edited by Boulton (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1958). Cf. John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Roger Woolhouse (London: Penguin, 2004), Book 2, Ch. 21, Par. 16: 219. ↩

- [5] A similar economy is present already in the very concept of “passion” as it is conceived by Aristotle or Descartes, insofar as passion (pathos) is thought to be the “passive” correlative of an active impression according to some principle of energy conservation. See Aristotle’s treatise On the Soul: “all sense-perception is a process of being […] affected” (424a; Book 2, Part 11), trans. J. A. Smith (http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/soul.html). Descartes opens his discourse on The Passions of the Soul with the same idea, as he starts out from the co-determination of passion and action; see René Descartes, The Passions of the Soul, trans. Stephen H. Voss (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989), 18-19. ↩

- [6] In fact, a very similar notion, that of indifferency, does exist in Locke’s terminology, but it appears in a different context, attached to the notion of liberty, and does not bear on his own conceptualization of the passions of pain and pleasure in any significant way (see Locke, Essay, Book 2, Ch. 21, Par. 71: 257-259). The notion of indifference plays a more important role in the early Greek hedonist school of the Cyrenaics, founded by Aristippus of Cyrene, who held that sensations can be subsumed into the three categories of pleasure, pain, and indifference, depending on whether the impulse is gentle, violent, or calm. ↩

- [7] This adjective makes its appearance only in the Introduction (18) to the second edition of the Enquiry in 1759, where it appears in apposition to “indirect.” In the main text, Burke keeps speaking of “relative” pleasure or pain throughout. For Kant, the notion of negativity informs the concept of “negative pleasure” as well as that of “negative exhibition,” see Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis – Cambridge: Hackett, 1987), 98 (cf. 129) and 135. ↩

- [8] The distinction between the two forms of relative pain is drawn in terms of the temporary or final nature of loss: in the case of disappointedness, there is still hope to recuperate the pleasurable object, whereas grief is a state of mourning over an irreversible loss (cf. Part 1, Sect. 5: 37). ↩

- [9] This notion appears in fact at the very beginning of the Enquiry, when emphasizing the importance of novelty Burke describes repetition’s negative effect on effectiveness: “the same things make frequent returns, and they return with less and less of any agreeable effect” (Part 1, Sect. 1: 31). A similar description of repetition had been offered a decade before by John Baillie, in his “Essay on the Sublime” (1747): “Admiration, a passion always attending the sublime, arises from uncommonness, and constantly decays as the object becomes more and more familiar,” see John Baillie, “An Essay on the Sublime,” in The Sublime: A Reader in British Eighteenth-Century Aesthetic Theory, eds. Andrew Ashfield and Peter de Bolla (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 91. ↩

- [10] Burke connects the beautiful (i.e. positive pleasure) to the feeling of love: “By beauty I mean, that quality or those qualities in bodies by which they cause love, or some passion similar to it” (Part 3, Sect. 1: 91); “the beautiful is founded on a mere positive pleasure, and excites in the soul that feeling, which is called love” (Part 4, Sect. 25: 160). If the beautiful implies the intimate immediacy of love, then the sublime feeling of respect (i.e. negative pleasure) might be considered as a sort of tele-love, in which the threatening object is always respected “at a distance” (Part 3, Sect. 10: 111). According to Burke, we relate to objects of love by looking down on what is weaker than us, and to the objects of respect by looking up to what is stronger (Part 2, Sect. 5: 65-67). The same attitude manifests itself, in relation to the sexes, in the love for (weak) women and the respect for (strong) men, while in relation to generations, it appears as a cordial kindness toward grandparents and a reverence toward parents. From the juxtaposition of these two areas (the sexes and the generations) it becomes clear that a mother cannot be a “parent,” and a grandfather cannot be a “man” (Part 3, Sect. 10: 111). For Burke, mothers are per definition girls, and grandfathers are per definition castrated. ↩

- [11] In this, he is following Locke: “pleasure operates not so strongly on us, as pain” (Locke, Essay, Book 2, Ch. 20, Par. 14: 218). ↩

- [12] Just noting: it is by no means necessary to follow Burke in his zeal for the sublime. In a certain respect, his concept of beauty is just as, if not even more, thought-provoking. From the perspective of theatricality, one could easily show that the conception of the beautiful leads us to steeper slopes than those the sublime could ever reach, precisely because, unlike sublime “precipices” which at least give us a chance to locate and evade them, beautiful “slopes” are more difficult to cope with, because their seductive gravity is less discernible. At one point, Burke himself acknowledges that the alleged weakness of women, which generates their beauty, is not without a certain theatrical performativity (Part 3, Sect. 9: 110), one which is intricately related to the “deceitful maze” of the female body considered as a surface which captures the male gaze precisely with the “easy and insensible” variation of its forms (Part 3, Sect. 15: 115). Burke formulates his insight in a concluding question: “Is not this a demonstration of that change of surface continual and yet hardly perceptible at any point which forms one of the great constituents of beauty?” (ibid.; my emphasis). To confine myself to a single comment: change is hard to perceive precisely because it is continual. – I am trying to take steps in this direction in the framework of another essay, on “Terror(ism) and Theatricality,” focusing on Burke and specific segments of contemporary theory. ↩

- [13] This reading can be supported by other passages in Part 1, where a similar notion of distance is present without any reference to the difference between spatial or temporal aspects: delight is defined as “the sensation which accompanies the removal of pain or danger” (Part 1, Sect. 4: 37), implying that one’s life is “out of any imminent hazard” (Part 1, Sect. 15: 48), in other words, that we can perceive the terrifying object “without danger” (Part 1, Sect. 17: 50). ↩

- [14] Just as Burke (and Addison), Kant also lays emphasis on the key element of safety in the experience of the sublime. The Burkean notion of “immunity” is smoothly translated into Kant’s idea of “resistance” (Widerstand). What is, however, unique about the Kantian conception, is the way he splits the very concept of fear into two crucially different concepts, distinguishing sublime fear (fear from a safe distance) from panic fear (fear without safety). To fear God is sublime, but to fear “of” God has nothing sublime about it: “Thus a virtuous person fears God without being afraid of him [So fürchtet der Tugendhafte Gott, ohne sich vor ihm zu fürchten].” This conceptual distinction prefigures another one, to be introduced a few pages later, between religion and superstition. The Kantian sublimation of fear into sublime or religious fear (fearing God without fearing “of” God, Gott fürchten ohne sich vor Gott zu fürchten, to put it succinctly) presupposes that the person fearing is at a safe distance from the threat of God’s will. As Kant puts it, he “does not think of wanting to resist God and his commandments as a possibility that should worry him” (or, in relation to natural disasters: “provided we are in a safe place [Sicherheit]”). See Kant, Critique of Judgment, 120; Kritik der Urteilskraft (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1974), 184-85. ↩

- [15] In fact, the same oscillation is present within the latter section itself, as it opens with a definition of the sublime in terms of “pain, and danger,” only to underline later, in the passage I quoted, the necessary distance from “danger or pain” (Part 1, Sect. 7: 39 and 40). ↩

- [16] The notion of a “simply painful” effect also returns later in the discourse (see Part 1, Sect. 14: 46, and Part 2, Sect. 21: 85). ↩

- [17] The most recent German translation of the Enquiry translates “apprehension” as Sorge (concern or worry), see Edmund Burke, Philosophische Untersuchung über den Ursprung unserer Ideen vom Erhabenen und Schönen, trans. Friedrich Bassenge (Hamburg: Felix Meiner Verlag, 1989), 91 and 171. I mention this to open Burke’s discourse to the Heideggerian discussion of Sorge, either as a concern about this or that particular entity, or as concern as such without any specified object to be concerned about. This double aspect of Sorge could be articulated along Heidegger’s distinction between fear (Furcht) and anxiety (Angst) (see especially §68 in Being and Time, and more specifically, the subchapter on “The Temporality of Disposition [Die Zeitlichkeit der Befindlichkeit]”). While no such distinction seems to inform the Burkean definition of fear as apprehension, the disposition of anxiety is a permanent threat whenever the spectral nature of the object of fear is considered, most notably, in the potentially threatening aspects of the beautiful (see fn. 11 above). Thus, it is the very distinction of fear from anxiety which is problematic for Burke. One could conclude that it is the spectral contamination of fear and anxiety (the contamination of the two aspects of Sorge), which constitutes Burke’s “concern.” ↩

- [18] On the late 18th-century conceptual history of anaesthesia (its transition from a perceptual deficiency to a medical procedure), see Steven Bruhm: “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics at the Revolution,” Studies in Romanticism 32 (Fall 1993), 399-424. For other investigations into the conceptuality of anaesthesis (and its relation to aesthesis or perception), see the rich work of Odo Marquard and Wolfgang Welsch. ↩